Each year Dictionary.com and Oxford Dictionaries pick a Word of the Year that “embodies a major theme resonating deeply in the cultural consciousness over the prior 12 months.” Of all the words they could have chosen, this year, influenced by the presidential election, the words “xenophobia” and “post-truth” were given the star treatment.

Both dictionary organizations chose their specific words because they felt they both had been major headliners for (liberal) news stories in 2016, and had seen a drastic increase of word lookups after the U.K. left the European Union (Brexit) in June and after then presidential candidate Donald Trump secured the Republican nomination in July. In a blog post, Dictionary.com explained stories such as the U.K. leaving the European Union, the Syrian refugee crisis and France banning burkinis (which was later overturned) were perfect examples for the xenophobia.

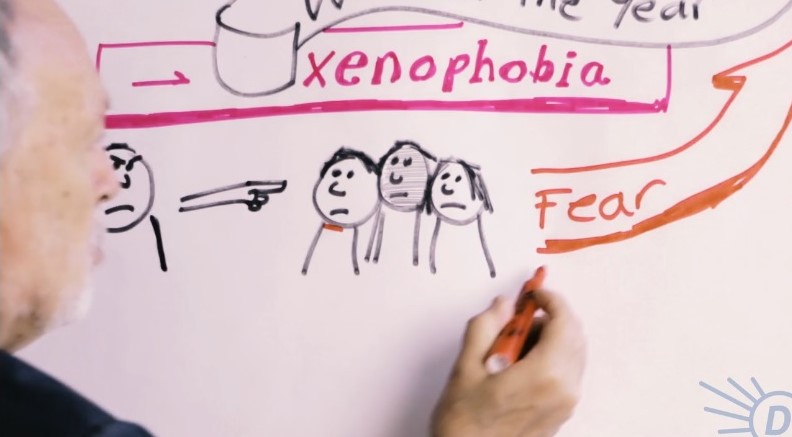

Xenophobia, as Dictionary.com defines it, is “fear or hatred of foreigners, people from different cultures, or strangers. It can also refer to fear or dislike of customs, dress, and cultures of people with backgrounds different from our own.” Of course, the media and the left’s talking points tried hard to make sure the word “xenophobia” and “Donald Trump” were used in the same sentence, as if to create a subconscious kneejerk reaction (think: Trump = xenophobia).

Xenophobia, as Dictionary.com defines it, is “fear or hatred of foreigners, people from different cultures, or strangers. It can also refer to fear or dislike of customs, dress, and cultures of people with backgrounds different from our own.” Of course, the media and the left’s talking points tried hard to make sure the word “xenophobia” and “Donald Trump” were used in the same sentence, as if to create a subconscious kneejerk reaction (think: Trump = xenophobia).

Dictionary.com proved how liberal this selection was by making a video with ultraliberal professor (and former Clinton Labor Secretary) Robert Reich, where he lectured about how some American politicians use fear to get votes, and create atmospheres of bullying and harassment.

In an article about Dictionary.com’s pick, Vox’s German Lopez opined that the events of 2016 were “in part a backlash to the identity politics of the past several years.” He continued: “Seeing the growth and rising acceptance of immigrants and minority groups, many white people—used to holding the power of the majority—have fallen back on candidates and policies that reject the ‘other.’”

According to Jack Holmes of Esquire, “deplorable alt-right cucks spreading fake news made 'xenophobia' the word of the year.”

Meanwhile on the other side of the dictionary fence, Oxford cited the grueling presidential campaign and all the hours the media spent fact-checking on which presidential candidate told the truth and who didn’t.

The dictionary defines “post-truth” as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” Take a guess on who they found to be the most “untruthful.” As The Washington Post explained,

“We concede all politicians lie,” conservative columnist Jennifer Rubin wrote in September. “Nevertheless, Donald Trump is in a class by himself.”

She cited The Atlantic's David Frum, who described Trump's dishonesty in May as “qualitatively different than anything before seen from a major-party nominee.”

None of this seemed to matter significantly to those who supported him.

“Alt-right” was the runner-up to both Dictionary.com and Oxford’s “Word of the Year.” “Alt-right” is defined as “an ideological grouping associated with extreme conservative or reactionary viewpoints, characterized by a rejection of mainstream politics and by the use of online media to disseminate deliberately controversial content.” Another word the media often uses with Trump’s name.

How ironic. Both words that Dictionary.com and the Oxford Dictionary chose, in addition to their runner-up word (alt-right) all have negative connotations and have been associated with Trump, thanks to the help of the liberal media. Is it any wonder why these words were chosen as their “Word of the Year?”